Suicide pods now legal in Switzerland, providing users with a painless death

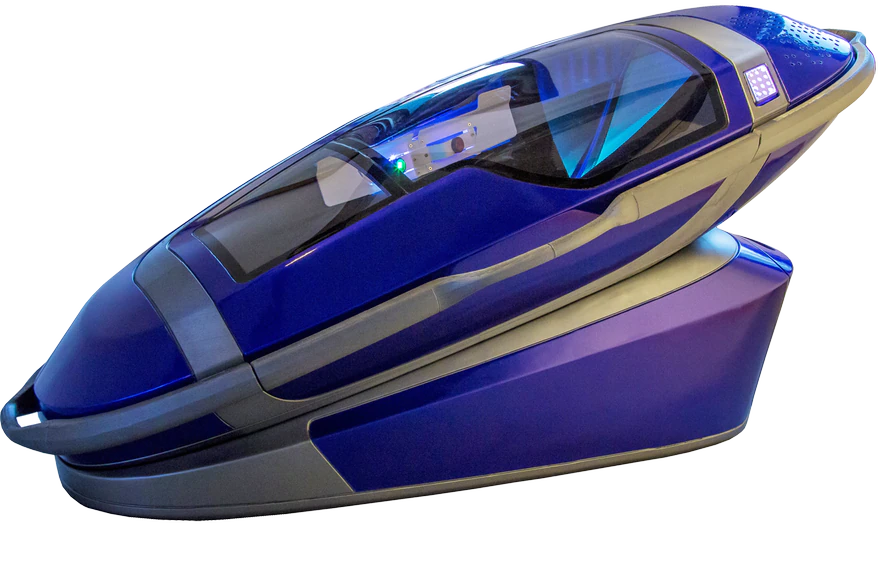

Switzerland is giving the green light to so-called “suicide capsules” — 3-D printed pods that allow people to choose the place where they want to die an assisted death.

The country’s medical review board announced the legalization of the Sarco Suicide Pods this week. They can be operated by the user from the inside.

Dr. Philip Nitschke, the developer of the pods and founder of Exit International, a pro-euthanasia group, told SwissInfo.ch the machines can be “towed anywhere for the death” and one of the most positive features of the capsules is that they can be transported to an “idyllic outdoor setting.”

Currently, assisted suicide in Switzerland means swallowing a capsule filled with a cocktail of controlled substances that puts the person into a deep coma before they die.

But Sarco pods — short for sarcophagus — allow a person to control their death inside the pod by quickly reducing internal oxygen levels. The person intending to end their life is required to answer a set of pre-recorded questions, then press a button that floods the interior with nitrogen. The oxygen level inside is quickly reduced from 21 per cent to one per cent.

After death, the pod can be used as a coffin.

“We want to remove any kind of psychiatric review from the process and allow the individual to control the method themselves,” Nitschke said. “Our aim is to develop an artificial intelligence screening system to establish the person’s mental capacity. Naturally, there is a lot of skepticism, especially on the part of psychiatrists.”

“The benefit for the person who uses it is that they don’t have to get any permission, they don’t need some special doctor to try and get a needle in, and they don’t need to get difficult drugs,” Nitschke said in a Sarco demonstration last year.

Nitschke said his method of death is painless, and the person will feel a little bit disoriented and/or euphoric before they lose consciousness.

He said there are only two capsule prototypes in existence, but a third machine is being printed now, and he expects this method to become available to the Swiss public next year.

In a 2018 personal essay for HuffPost, Nitschke said his focus in the realm of assisted suicide has shifted over the years “from supporting the idea of a dignified death for the terminally ill (the medical model) to supporting the concept of a good death for any rational adult who has ‘life experience’ (the human rights model).”

“Time and again, we see the comfort and reassurance that is gained from knowing one has an ‘exit plan,’ so to speak, within reach, should the need ever arise. Being in control gives confidence. It restores one’s sense of self. And, yes, it generates dignity in living, knowing one will have dignity in dying,” he wrote.

Nitschke added that people who use the capsule will not feel any type of suffocation or choking in the low-oxygen environment. Rather, they will “feel their best.”

Assisted suicide is also legal in the Netherlands, Germany, Belgium, Luxembourg, and Canada.

Almost 7,600 Canadians received medical assistance to end their lives last year, continuing a trend of steady annual increases in cases since the procedure was legalized in 2016.

That’s up 17 per cent from 5,631 assisted deaths in 2019, a number that itself was a 26 per cent increase over the previous year.

Justice official Joanne Klineberg told the Canadian Press earlier this year the number of cases will likely increase again as a result of recently passed legislation that expanded access to assisted dying to people who are not nearing the natural end of their lives.

She said cancer was the most commonly cited illness associated with requests for assisted dying in Canada last year, while the most commonly cited manifestations of suffering were the inability to engage in meaningful activities or perform activities of daily living.

The majority of applicants for assisted dying had received or had access to palliative care but felt their own suffering could not be relieved by that or other medical interventions, she said.

Canadian psychiatrists’ attitude toward medical assistance in dying for people with mental illnesses appears to have undergone a sea-change over the past five years.

When Canada first legalized assisted dying in 2016, a survey of its members by the Canadian Psychiatric Association found 54 per cent supported exclusion of people suffering solely from mental illnesses.

Just 27 per cent approved, while another 19 per cent were unsure.

But in another survey of its members conducted last October, a plurality of respondents — 41 per cent — agreed that individuals suffering only from mental disorders should be considered eligible for medically assisted deaths.

Thirty-nine per cent disagreed, while 20 per cent were unsure.

—With files from The Canadian Press

Original article found here

Dejar un comentario